One year ago I chaired an English Department and taught writing courses at a small college. When not dealing with administrative red tape–which was all too common–I worked at revitalizing a curriculum, rekindling a departmental vision, banishing plagiarism, and most importantly, cultivating ideas and empowering students’ voices. I felt that my labor was meaningful. Sometimes my sense of meaningfulness arose as a result of positively impacting a few students’ outlooks on their places in the world. But, when I struggled to connect to the larger population of students, a much more common occurrence, what meaning I could muster was there because society tells me that teaching is meaningful and noble.

Today I am no longer a teacher. Today I am a student, one who is learning to cultivate earth rather than minds. I am relearning the art of farming, an art practiced by my forefathers beginning with my family’s federal land grant on February 1, 1827 (189 years ago today). Like my ancestors before me, my labor is shoveling manure, moving bales of hay, and carrying buckets of feed and water. Although society knows food is valuable, and encourages meaningful connection to the earth, somehow the pursuit of cultivating land is not the lauded or sought after profession that my forefathers so proudly embraced.

One of the biggest differences I’m coming to terms with is the nature of time. In college, the unit most often used to measure time is the 15-week semester. As a professor, I assigned students homework. I collected that work (mostly) on time and (mostly) completed. I gave students comments and helped them understand the grades they earned. And as soon as one semester ended another one was just beginning.

I haven’t even been an apprentice farmer for more than 15 weeks yet, but already I’m finding that the scales of time I’m being asked to consider–seasons, years, decades, centuries–demand a deeper consideration for longevity, sustainability, and connectivity than I’ve ever experienced before. As an apprentice farmer, I have seen a sow give birth and experienced the fragility and yearning of new life. I have seen a calf weaned from its mother and experienced the vitality and promise of newfound maturity. I have seen a goat die and experienced the uncertainty of life and the spontaneity of death. So many experiences, and not even a season, the smallest unit for measuring time on a farm, has passed.

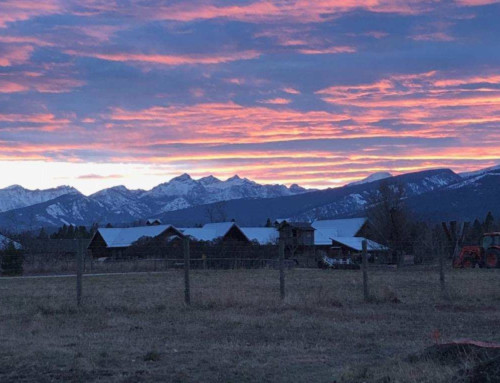

And yet, already I can see my labor–shoveling manure and moving hay, helping with earthworks projects and seed starts–translated into healthier soil and happier animals. I see the ideas/ideals of stewardship and respect translated into actions. Within my seemingly simple farm labor I am finding the seeds of expressiveness and honor and hope. This journal will be a record of my journey away from ivory towers and towards green pastures, away from cloistered classrooms and towards fecund fields. This journal is my attempt at rediscovering my farming heritage, finding a fluid existence between teacher and student, and understanding what it means to cultivate the earth in the 21st century.