Moving forward, I will be trying out a different genre each week. My hope is to see what unique opportunities are offered by each genre for processing my time on the farm. Here is the current schedule:

1st Monday: fiction (today!)

2nd Monday: reflection

3rd Monday: poetry

4th Monday: open letter

***

The land Beck purchased hadn’t ever been a farm as far as anyone in the community could remember. It was waste land: oddly shaped with irregular outcroppings of rock jutting up randomly across the parcel, and untamed brush exploding up out of the ground everywhere else. The rocks on Beck’s property were covered with lichen–golden and green and rust colored. They crunched when stepped on and always seemed too dry to be alive. And there were tangles of brush, the sages and the chickweeds. These were plants that fought back. They ensnared the graceless and pincushioned the careful. They were the land’s crusty sentinels, standing a weathered watch.

The first time I met Beck he was waist deep in a hole, a pit really, that he had smashed into the earth itself. It was deep into autumn but the days were still warm. It’s dry here, and when the sun is out, the land starts to bake. A crust develops like withered skin—dry, soft, and ever so fragile. But beneath this thin surface the land is rich and deep. But the land makes no apologies and hides little, constantly pushing new bits to the surface, constantly refreshing itself through the seasons, exposing some things but hiding others deeper in the process. And those secrets the land decides to keep it buries deep.

From the look of things Beck had been hammering at this particular rock outcropping for several days. As I approached unnoticed the severity with which Beck pummeled the rocks was evident. Sweat dripped from his face like a man working at a forge. He hammered as if the earth was an anvil upon which he beat at the lump of himself. He hammered as if to dent and rend himself unrecognizable, as if by demolishing what was he could then somehow continue hammering and in the process force a new reality in to being. He worked like a man who had run out of time and who was now trying to finish his task before the lights were turned out forever. From his efforts one was able to see his marks upon the land as one sees the warp and the weft of a fabric, and hear his hammer blows as one hears the clack of a shuttle as he worked to expose and tear apart–but also to create and discover–something with his labors.

I found out later that after the incident Beck got in his car and just drove. Whatever wouldn’t fit in his car either went into the dumpster or to Goodwill. He had no space, either in his car or his head, for the things of the past. After only knowing him for a short time I learned that Beck always drove with the windows down regardless of the weather. I didn’t ask, but my suspicion was that he’d driven across the country like that. He said he had to feel the air on his face, had to smell it. This made sense, I suppose, what with his muted right side and the driver’s window on his left. He always seemed a bit out of sorts whenever I drove and acted somehow unplugged or disconnected. He seemed unable to stay grounded in the moment. I didn’t dive very often.

Privately, I always thought that Beck left part of himself behind, severed part of himself, as a sacrifice, in order to get away from that other life. I imagined Beck’s leaving was like tearing your tongue off of a frozen flag pole after being dared to see if it would stick. Or perhaps it was more like wrenching your hand away from a scorching pan after leaving it touching for too long, not registering the heat until it was too late. Secretly, we always know that our skin will stick, will burn and tear. We know this fact before we try to get away, get out, get free. But for some reason we still dare the universe to do it to us, too. We’re sure that unlike those who came before us, those broken-down cynics, we will get away unscathed. For Beck, though, his pound of flesh was his sensitivity, his connection to the world, which he had to offer up in sacrifice, in exchange for freedom.

I’ve sometimes wondered if I wasn’t seeing things from the wrong end. What if that part of Beck that I was seeing as torn away—the left behind part—was the real Beck? What if the Beck I know here on the farm is actually the part that was discarded because it didn’t fit, because it unbalanced the calculus of “life out there,” because it “stuck” too much to life? What if the Beck I know is the sacrifice? What if he is the remnant given over to the world so the rest could be accepted into the system without conflict, without rejection?

After weeks of hammering he found the vein. It was as if he had peeled back the skin of some enormous giant, dug until he exposed its bones, and, when he had finally broken them, feasted on the marrow of the earth. Beck uncovered the iron vein in one final triumphant shout of fury and ring of hammer and crack of rock. From all of his hammering and sweat and rage he had found something the land had secreted deep within itself. And upon realizing his discovery, he laid down his hammer, slumped against the side of the pit, and wept.

***

text © Andy Engel, 2016

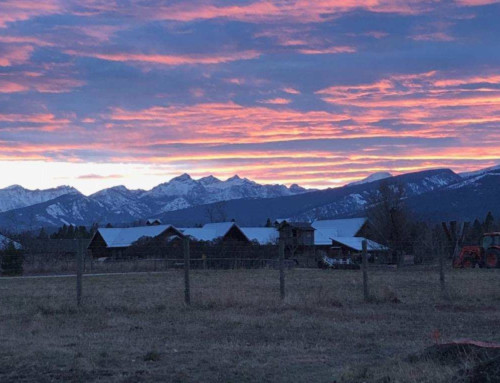

image © Brea Engel, 2016