Note: These weekly journals are a means for me to process the events of the past week and to archive my journey into the world of permaculture. This week’s offering is different. What follows is my first attempt at using fiction to process my experiences. Carl Abbott, for example, argues for the use of fiction as a “sandbox,” a way of expanding our imagination and helping us see new possibilities. In this way I hope to use writing, and the writing process, not just as a way for sifting through what has been, but also to begin imagining what might be. Currently, the plan is that these fiction installments will be monthly. Stay tuned.

***

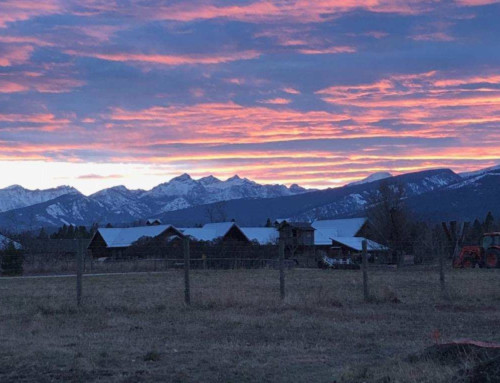

Dawn shatters across the mountains. As the sun rises higher its light marches across the valley back to the source. A fog lies heavy in the valley–thick and dense and leaden. The air has a weight, a sense that you could hold it, contain it, if only you could grab a larger handful. Skin prickles. Shivers run. Movements and contacts are electric. And the smell. The air is deep and moist, and even the smells from the farm animals are only rich and alive and inviting.

When the line of time–that separation point between light and darkness–reaches the bridge, the day begins. It falls on the bridge this time of year. Now and again in about six months. This summer the day will start when the line is at the treehouse. This fall it will begin at the goat barn where the babies are born. In the winter it will start in the empty field. Where the light touches, the ground shines golden. Motes sparkle. Frost encases and lends a glow to the everyday, to the useful, and to the common. It is a world suspended in glass, full of promises. Where the darkness remains the ground is pitted and pocked like the surface on the dark side of the moon. Its frozen craters form the thick crust of a landscape, one that seems like all the colors have been bled away until only the outlines and planes of objects are left.

Onto the section of the road still covered in darkness steps Beck. Beck is a man divided watching two worlds colliding and struggling for control.

No outward signs remain from the incident. To look at Beck is to see a man in his prime. He is tall and athletic with messy red hair. From the outside he appears strong and whole and ready. But for Beck, from the inside, the experience is different. He would not say he feels trapped. That would be too simplistic, too tangible. If he ever were to give the feeling a name, a description to his life after the incident, he would say that he feels muted. He feels a lack, a numbness, a sense that some incomprehensibly big hand reached in and turned down the volume on life, or maybe just shifted the L/R balance. Beck cannot feel anything on the right side of his body. The sensation, or rather its lack, is most acute at his extremities and fades closer to his trunk. The feedback loop between his body–or at least his right side–has been interrupted somehow. He can still move his limbs. He can still tell his hand and foot to move, but unless he’s watching them, he has no idea if they’re doing what he wants them to do.

The last time I saw Beck was years after the incident and his subsequent choice to move to the farm. But choice is the wrong word. I was never sure that Beck actually chose to be a farmer or if the incident chose it for him. In all the years I knew Beck, I never got a straight answer out of him. Perhaps he didn’t know either.

***

© Andy Engel, 2016