1st Monday Genre: Fiction

———

It was months before Beck went back to the pit after he discovered the iron veins. By the time he finally did return, during the lull between Thanksgiving and Christmas, the exposed veins on the walls were rusted a deep orange, striped magical and dangerous as a tiger. The pit stared back at him, waiting silent and patient. It paced in his mind, restless, promising nothing but the naked truth, cold and uncompromising but honest.

Leaving the pit behind, he spent months improving the farm. He rebuilt fences, tore down rotted wooden siding from the building he had taken to calling the barn, and ran pipes for frost-free hydrants. And yet despite the work he gave to himself, he often felt the pit calling to him, scratching at the back of his mind. He had broken through to something new and rich. There was a feeling—not anxiety but perhaps reverence for veins, for the earth—and Beck would have told you that he was refusing to rush into things. Really, though, I think it was more that he was unable to move forward, move deeper that summer. Something outside the pit remained undemolished and monstrous and its looming presence kept him away from the pit and the veins of the earth.

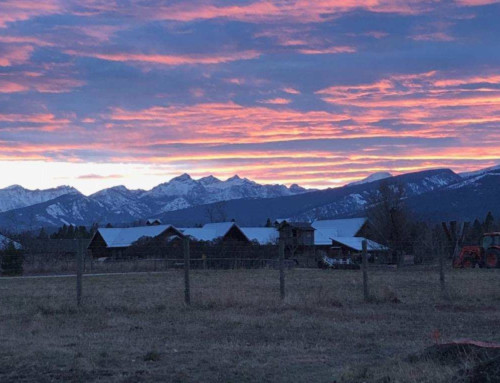

We told ourselves that there was simply too much to do. Too much living to be had rather than rattling around some hole in the ground. Beck spent most of the summer finding ways to stay busy. Then suddenly it was late-summer and the beginning of the early-harvest. These were the high days, well-earned. Everything and everyone was sunbaked and ripe. Laughter and music swelled. Drinks were poured and dances were danced. The sunset lasted a long time. The numbness that Beck felt on the right side of his body, the constant reminder about something lost or forsaken, was itself forgotten in the jubilance of new things. The numbness remained, but it occupied less and less space in Beck’s thoughts that first summer until it started feeling like this was always the way things were and always the way things were supposed to be.

During that first year, as summer gave way to autumn and then on into winter, Beck spent more and more of his days alone. His labors developed a methodical rhythm. Slowly at first and then with an increasing sense of urgency something changed. Into the moments when his arms and legs kept their steady pace and his mind was released from the demands of juggling the unruly expectations of life, somethings began to assert themselves. They came into the stillness as if called, like chittering coyotes keen to the scent of prey wounded and exposed.

It was during these quiet days that the specters came, uninvited. They clamored to be set free, to be given reason and room to cause friction, to provide a spark, to set it all—to set him—ablaze. They rumbled up from the depth of pasts that Beck didn’t remember having, or howled like ghosts from half-remembered dreams. These specters—these emotions and memories and dreams—felt like they belonged to someone else. For a while he tried to stop them, tried to push them away.

“These are not mine,” he thought. “I don’t want them.”

Finally, resigned, Beck let them come, he had no other choice. He accepted that they were now his, shackled to him, dragging him deeper. So instead, Beck forced himself to be still. He let the specters accumulate like tinder inside a chimney box. He let them crash and pile upon each other, each jangling louder than the last, demanding his energy. Then finally, among his hushed labors, he set them alight with all the smoldering fires of his rage, and his joy, and his confusion, and his sense of betrayal. He gave it all away, added his breath to the fires’ heat, and put his world to the torch. Like the cleansing sweep of a forest fire, Beck’s inner incandescence consumed these specters and they burned, ever so brightly. He burned them because he had to, because it was necessary. There was no other way to move, to keep moving, with them still clinging to him.

As more specters floated to the top of his still mind, the fires burned hotter, blazed brighter. They burned so hot and so bright that they burned him clean. They burned with the threat and the promise of release. He let the specters burn and consume themselves until they were gone, so that if they were somehow ever remembered again it would be only as vapor and ash. Nothing remained but fragile sculptures made of dust, ready to be set to the winds with one last breath and then he would be free of them.

It was during these days of stillness and specters that, to Beck’s surprise, he noticed a tingling. He was struck that despite the fires inside him he felt the pins-and-needles sensations of a body remembering that it still breathed and walked and pushed back against and flowed into life. The sensation was slippery, just a whisper, and then it was gone.

***

text © Andy Engel, 2016